Distraction, Disillusion, and Disregard

The Three Ds of How the World Will Attempt to Break You

Over the past two weeks, I have noticed a significant uptick in subscriptions to this blog. I am both happy and deeply humbled to see this. If you’re digging Rambler and want this community to grow, please click the share button below!

If you are new to the blog, going back into the archives won’t help you get a sense of what my overarching goal is for this project, but it might give you a sense of my style, or else a brief window into what I’ve been up to the last few months. I have tried, at times, to give updates about my Fulbright year, but mostly I’ve been working on developing a personal philosophy, sharing what works for me and what might work for some of you. I am seven months into this experience teaching abroad and I’ve learned a lot. I don’t always reflect directly on that here, but the particular setting is still relevant context for each post.

This is all to say I’ve had a lot on my mind lately which can be great for my writing provided I don’t get sidetracked, or else overwhelmed. There are three competing forces that can derail any writer: distraction, disillusion, and disregard, and it seems to me that it’s how we respond to these forces that directly impacts the quality of our lives. Today, in a tripartite post, I give you: the three D's of how the world will attempt to break you (and how to make sure it doesn’t). Fun, right? Let’s begin.

Disregard

Something like five-plus years ago, a rising senior (whose name I can’t recall) addressed my incoming class at Geneseo’s convocation ceremony. The one line that sticks with me to this day went something like “the opposite of love is not hate, but indifference.” Before we quibble over semantics, let’s consider what this might mean and how true it really is. The world, though it may seem sometimes intent on breaking your very soul, does not and cannot hate you. It is a cold, indifferent world that thinks not of your existence and is therefore not spiteful but merely indifferent. If you’re agnostic about the whole idea of a higher being, as I am, then the nagging question of “why” is like an itch that cannot ever sufficiently be scratched. What is the meaning of life if the world is nothing but a small blue dot adrift in a galaxy of other, colder, even more indifferent dots?

In many ways, this question misses the point and can quickly become navel-gazing, or else profoundly radicalizing in all the wrong ways. But it remains eternal. To me, if there is no God, and if the world is truly indifferent as it often feels, then the meaning of life is love. Why? Because out of this nothingness that surrounds us we have a chance to create something through love that is bigger than ourselves, transporting us to a higher plane of existence that I imagine the devout feel when they commune with their god. So, in this way, the opposite of indifference is love and, it stands to reason, that the opposite might also be true.

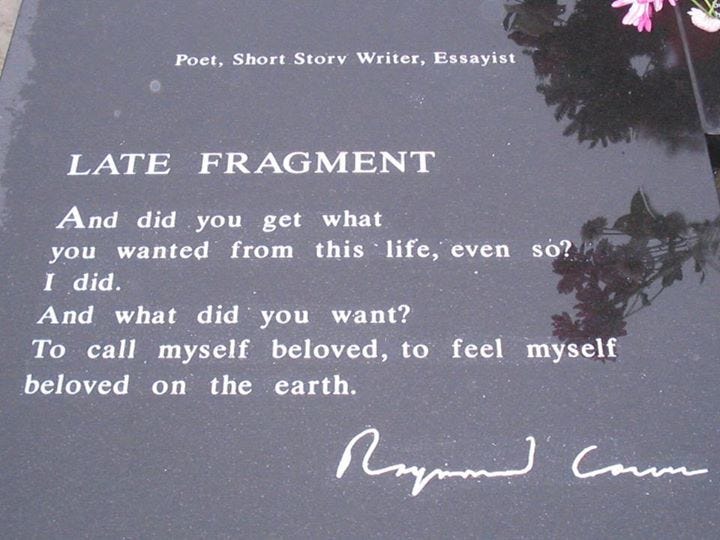

Big talk from a single twenty-something with a blog and bad caffeine habit, no? Then consider what we mean, or (please forgive me), what we talk about when we talk about love. Here, I don’t just mean romantic love, or even love for another human being. I mean the intensity we give to things which we love, the devotion to the practices that make us feel most ourselves. Most importantly, to whom or what do we constantly return even as the world tries to stand in our way? Those might be objects of our desire, which is different, but they might also be recipients of our love.

So, those among us who cherish another despite their seeming faults know love. So too do those who would rise on a Sunday morning for worship, or a long run, or simply a communion with family and friends. When the weather is punishingly cold and the bed you lie in is so very warm, the meeting of the moment is not only a product of love, it is how we define ourselves when the world appears indefinite.

I, too, spoke of kindness in the face of indifference once, at my high school graduation, and I stand by a lot of what I said then. Something which that 18-year-old atheist could not anticipate, though, was the messiness of adult life that challenges kindness on a daily basis. If we get such peace and joy from being kind, then we might quickly convince ourselves that being kind is in some ways selfish, or that there ought to be limits to things like forgiveness and love. Consider these softer categories from the analytic angle of evolutionary biology. Kindness, or more general agreeableness, can help an individual survive, afford them the protection of tribe, and act as a shell of self-preservation, allowing a gene to survive and advance. In The Second Mountain, David Brooks asserts that the “the will is problematic. It is self-centered. It tends to see all of human existence as something that surrounds me, as something in front of me, beside me, and behind me.” He goes on to say note just how quickly kindness can become charity, something we use not to serve others but to pad the ego, to warm the self.

Conversely, the selfish gene hypothesis put forth by Richard Dawkins, paints us all as rational actors, putting our own interests before those of others. Things like love and kindness are, in this view, just semantic cover-ups for an arrangement of chemicals in the brain and body which help us get ahead. I embraced a lot of this scientific understanding myself and there is evidence that practicing things like gratitude can improve our overall well-being (I would normally link to a study here, but instead, just try it yourself and watch your mood improve).

The trouble with the strictly scientific view here is that we know that humans are not always the most rational creatures. Further, there is an undeniable, if inarticulable, difference between the way things are and the way we perceive them. The kindness that must be demanded of ourselves is a much more radical one. It is refusing to collapse into indifference and seeking to live above it all. It is connected with other Rambler themes of abstention in a society of consumption, love in the face of hate, and focus in a world of distraction.

Distraction

I do not have to tell you all that we are, as a society, more distracted than ever. Your cellphone simply has to buzz and just like that you’re done reading Rambler. In fact, I don’t have to tell you most of these things, but I do so for two reasons. The first is that there is power in affirmation and repetition. The devout, unshaken in their faith, still go to church every Sunday. The second reason is that, though it might seem odd for me to be giving you all advice, that’s not really what I am doing here. Instead, I am trying to figure out what is true for myself by exploring what is true for others. In The Second Mountain, Brooks writes “those of us who are writers work out our stuff in public, even under the guise of pretending to write about someone else… we try to teach what it is that we really need to learn.” I haven’t the moral certitude, yet, to deliver soliloquies, so I write tentative propositions instead, hoping their resonance affords them some truth.

In many ways, distractions might be the most difficult of the three Ds to break from. First, while it might not have the moral weight of disillusionment or disregard, distraction is far more constant, always humming in the background, ready at any moment to pounce on our attention. We go through bigger boom-bust cycles with disillusion and disregard: we fall in love, or out; we find truth in a religion or philosophy, and then it’s punctured. Distraction, in the forms of social media or food marketing, offers the same appeal to all as it hacks our very biology.

Psychologists now agree that non-substance addictive behaviors such as gambling, pornography, and even compulsive internet use are just as legitimate afflictions as addictions to chemical substances (it’s in the DSM-V!). Distraction is not nearly as physically corrosive as opiate addiction, but the mechanisms it exploits appear to be the same.

What’s worse is that distraction breeds distractibility. The more we divide our attention, the more divisible it becomes. It seems like this should be mathematically impossible, and I assume that the endpoint of such division is the arrival at something like burnout or worse.

What then can snap us out of distraction if willpower no longer seems a legitimate tool? Willpower might have worked when the distraction war was fought with tabloid papers and flashing neon. I am reminded of a quote from William Randolph Hearst that feels almost quaint now which goes something like “I don’t sell newspapers, I sell advertising.” In the grand scheme of things, with the proliferation of different and more advanced media, skipping the newspaper stand doesn’t require much willpower. But now the weapon of the distraction war rests in our pocket all day long, set to go off at any moment. We require something more than willpower to dismantle it.

I think it comes down to reevaluating our balance of work and leisure and rearranging ends and means. The more we allow technologies of distraction to gamify work and rob leisure of, well, actual leisure, the harder it becomes to even see the problem as a problem. Apps that would have you exercise, meditate or study only for the sake of maintaining a streak are great at committing you to a regiment, but they reverse means and ends, corrupting the process and diverting our focus from the personal goal of mastery to the technology’s goal of increased users, and therefore profit. The reevaluation thus requires that we do away with those activities that are only maintained on the basis of score-keeping; or, at least, doing away with the scorekeeping.

The next step is filling the time saved on cutting back with richer experiences. Cal Newport and David Brooks both remark on the necessity of finding new alternatives to distraction because the pull of distraction is too strong to simply remove without a replacement. I’ve tried myself, implementing site blockers that do nothing except drive me to other sites. Brooks is a little extreme, but there is some truth in what he says: “do not flatter yourself in thinking that you’re brave enough to see into the deepest parts of yourself. One of the reasons you are rushing about is because you are running away from yourself.” In my experience, the more I isolate myself the more I have to artificially manufacture relationships or habits that are by their very nature unsustainable. Thus, reminding and recommitting ourselves to that and those which we love is a crucial part of leading a focused life.

Disillusion

Psychiatrists in the Czech Republic are warning that a stage of disillusion might quickly follow the phase of solidarity that first met the Ukrainian refugee crisis. Read that again if you want to be depressed. I am not so sure such a phase is as “inevitable” as Jan Vevera and the like are, partly because of how he describes the stages preceding disillusion. Before people come to resent refugees, they first act “heroic…communities mobilize internal reserves, raise funds and volunteers get involved,” Vevera says. This so-called heroism quickly gives way to anger or frustration at the fact that many refugees don’t fit many people’s mental model of refugee, or so he claims.

Seven months ago, I had never met a refugee of war before and I only experienced conflicts such as the one in Ukraine when I read the news. Now, I live among a community of displaced individuals who cannot return home for any number of reasons. I have a Venezuelan colleague who, though she is not a refugee, remains in Europe partly because returning home seems like a dead-end. Or take, Ghassan, my neighbor from Syria, who came here to study but stayed when Assad took over. There is no one model of what a refugee looks like and the idea that one could forget why Ukrainian folks have arrived and instead resent their presence seems dubious at best to me. Certainly, there has been and continues to be an ethno-nationalist streak on the far-right side of European politics, but folks in this camp likely sympathized with Putin to begin with. It seems to me that the only way one might be truly disillusioned by what has transpired in Ukraine is if one is only hearing of it on the internet or through a steady diet of mainstream media.

Being rooted in a place is one such antidote to disillusion because it offers us agency and the tangible feeling of the impact that is hollowed out in movements that happen only online. I’m not saying that it’s impossible to care about those who you don’t know. What I am saying is that the more we recede from our communities the less we get to empower and feel empowered and thus remained steadfast in the causes that matter to us.

The internet can be a great place to learn about and help people around the world, and it has indeed leveraged more impact than almost any other technology in recent memory. However, one of the consequences of nationalizing and internationalizing our media ecosystem is the anxiety that one feels when it seems the whole world is in tatters, and because you are able to access such peril simply by scrolling and retweeting, the level of personal responsibility seems incomprehensible. We feel helpless in the face of such great calamity. Turning back to the community is one such way to reclaim a sense of self and to help others in direct and meaningful ways. Don’t turn off the TV or delete your Twitter account just because the news is hard to look at, but try and balance your impact by maintaining a connection to a physical place.

Every once in a while I forget I live in a foreign country, but it’s never at moments I expect, like when my students start reverting to Czech or when I cannot read something on the town bulletin boards. These moments have become more like water to a fish. Instead, it’s when I am alone, either at my apartment or walking home from work when I realize I am not of this place. I suppose solitude is more powerful than being the outsider when it comes to missing home. I think this speaks to the power of community and should exhort all of us to reinvest in the places and people that more immediately surround us. It is not from facing the day-in-day-out challenges of 21st life that we become disillusioned, it’s in turning away, in refusing to see what and who is out there that our causes become obscured.

The mantra “keep showing up” is something like an antidote to disillusion, but here at Rambler, we say something else….

Ramble on!

It’s so good to read your writing again Sean and you’ve provoked many thoughts. The Carver quote is among my favorites and I believe it is absolutely true. I hope you are enjoying teaching. Your students are so very fortunate to have you as their teacher.