I’d like to start by saying that if you recognized the subtle allusion to Cody Jinks, either you (1) are related to me, or (2) your name is Justin, Jimmy, or Jackie. In either case, hello there and welcome back to Rambler, I’m glad you’re here.

Like a lot of people these days, I consume far more music than I produce. I don’t fault myself or others; the sheer amount of music availabe to the average listener is greater now than any other point in human history. I only mention this to urge you all to take all of what I say with regards to music as nothing more than rambling fandom. I believe practicioners often make the best critics, and while I have tried my hand at poetry and short fiction to deepen my appreciation and sharpen my criticism, I am so utterly unmusical myslef that my opinions in debates on music are somewhat lacking in perspective.

Additionally, though the impulse to distrust expertise can at times be healthy, I think we ought to give experts more credit than we currently do and I also think that expert opinion on music can often be on the right track even if their opinions don’t gel with our own personal tastes and preferences. I am not about to suggest that music debates are somehow meaningless because the critics know best. Rather, I will simply assert that debates aren’t actually good for much. Or, better put, debates don’t actually achieve we want them to and that we should be okay with this.

A few months ago, I threw up an Instagram story that asked my followers a deliberately broad question: who was the greatest American punk rock band of all time? A steady stream of disparate answers filled my messages: Fugazi, FIDLAR, the Replacements (a personal favorite), Bad Brains; the list went on. What I learned is that punk is such a divided genre but the raging debates didn’t hamper the genre, instead they helped shape it into the cutting edge of rock music for decades.

You can’t convince a goth of hardcore’s raw power, not to mention that the whole debate seems ridiculous to fans of the more homogenizing genre of country music. Likewise, many of our current political debates often feel so futile precisely beacuse they are frame in terms of debates. This, not that. Two sides are pitted against each other in a competition which reduces complexity, making things like persuasion secondary to puritanical point-scoring. Twitter has even borrowed sports phrases like dunking to describe how our online debates are waged. I don’t know, maybe its because I was a cross country runner and not a power forward that I feel this tit-for-tat way of communicating mostly destructive to creative and political processes.

English class vs debate club

To supplement instruction, Fulbright Czech Republic asks that English Teaching Assistants set up some sort of extra-curricular club for students to practice in an informal setting. Past ETAs have held book clubs, played soccer with students, or worked on creative writing projects. I know of a current ETA running a debate club with her students which is an idea I entertained for a while before arriving in the Czech Republic last August. Many of these clubs, mine included, end up falling into much more fluid discussion-based meetings, extra English lessons without the written assignments or graded assessments. I suppose I took the easy way out when I decided to abandon the debate club idea, but I did so conscious of the fact that debates are actually much less generative than we might hope.

Recently, a colleague asked if I might start introducing debate speech into the classroom, but her students are some of the most advanced at the school so it quickly became less about the grammar and more about the content of the debates themselves. This troubled me for a few reasons. First, I am an English teacher and while I often enjoy grappling with debated issues with friends or on Rambler, my job is first and foremost to instruct on language and composition, not offer my opinions or the opinions of others. I know I can’t avoid certain debates and to not challenge misguided or even harmful beliefs does seem on some level irresponsible. However, I am doubtful that I am really going to, over the course of a few English lessons, see anyone change their mind. Second, the topics selected by my cooperating teacher are either so broad as to be innocuous or they are rather irrelevant to my particular cohort of students.

Last week, my colleague decided on gender equality as a topic for debate and I struggled mightily to think of what I might discuss with 15 young men (and two unfortunate young women), most of whom are preparing for a career in the heavily male-dominated Czech armed forces. This is not to say that men have little concern for feminism; rather, my military students are rather ideologically homogenous. I have attempted reading opinions aloud and having students move to different places in the classroom in order to facilitate these debates. More often than not, all of the students will migrate to the same spot, meaning no one will take up a dissenting opinion (what’s more is that if I were to take part myself, I would likely be the lone figure on the opposite side of the classroom). Therefore, I have to artificially and arbitrarily divide the class into two groups (as if there are ever only two sides to any debate) and have them come up with reasons, which are not their own, for staking one claim or another.

This can be great practice for trying to see things from another perspective, but it is also profoundly fun-sucking to students who do have an opinion and are being forced to withhold it in the name of learning grammar. Again, I realize that the point is not coming to a consensus but practicing different speech patterns in English, but with a group as talented as my fourth graders (high school seniors) the grammar is often blown past in pursuit of getting to the heart of the debate. And the last thing I want to do is stop them from speaking.

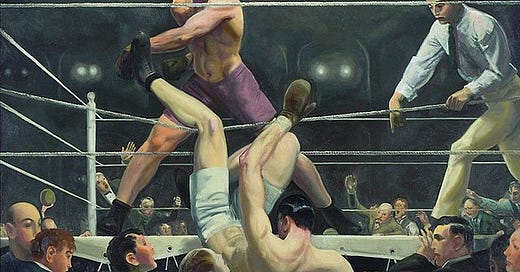

Sometimes I can’t tell if I actually despise debating or if I’m merely pessimistic about its efficacy. I think, at the very least, we should be skeptical of any medium that would arouse in our guts the same feeling of passionate intensity we feel when watching a basketball game or an episode of Jerry Springer. Debates, it seems to me, play more on our emotions than our intellects. If my heart begins to race during a debate then my mind is necessarily that much harder to reach, to appeal to.

In order to change your mind, you first have to be open to such a change and debates do not often take place in arenas of open minds. How many people still watch candidates debate on the campaign trail in order to make an informed decision on the ballot? Not only do we actively root for contestants on our side of the debate, we often process the arguments of the other side as evidence of our moral or intellectual superiority. Opposing viewpoints no longer seem enlightening; they are rather sticks with which to poke a dragon and we use the fiery reaction as grounds to dispel the other side as irrational or unthinking.

I’ve never been a part of any musical scene

I wanted to frame this post around popular music, namely the ways culture silos can create camps like punks, hippies, cowboys, and metalheads because besides making anodyne gestures towards Bob Dylan when asked about influence, all of these groups really do have a lot in common. It might seem obvious, but beneath all of their disparate styles remains a belief that music is fundamentally a meaningful act of creation and the particular form it takes it secondary to the expressive act. In this short animation of Jeff Tweedy the leadman from Wilco describes what he sees as false dilemmas all around music and culture more broadly. The more musicians and fans seal themselves off from other musical subculutre, the less creative respective genres sound.

In fact, I think the musicians themselves know this quite well. I was scrolling through some playlists put together by one of my favorite contemporary rock bands, Twin Peaks, and was surprised to find out they are absolutely enamored with Motown. Now, I didn’t then become an instant Motown fan myself, but this discovery made me reflect on how the wars between punks and hippies is largely based on a myth that has no basis in the music itself. If you open up instead of shut out other styles of music you begin to hear things in the music you love you would otherwise be deaf to and new artistic discovery is one of the most electrifying feelings (if you ask me).

There’s a scene in 20th Century Women where Jamie’s mom’s Volkswagen is defaced with Black Fag graffiti and she cannot comprehend why fans of that band would wreck the car of a Talking Heads fan. To me, its important that the war rages among fans while performers as different as Bob Dylan and Gene Simmons seem to draw on each other’s styles all the time.

Stronger than the subjective suggestions of our favorite artists, though, are the “You Might Also Like” features many streaming services now employ. These algorithms appear relatively benign and it might even feel cool to follow along as you begin to develop a taste profile, a musical identity. However, you should always keep an eye on your role in this process. In other words, to some extent, our tastes and preferences are often made for us under the guise of subtle suggestion. The thing these algortithms do is turn culture into another arena for debate instead of harmony. In a partly sadistic experiment, Spotify ought to replace this feature with a “You Might Really Hate” feature to stoke more creative listening and to puncture the myth that punks don’t listen to metal or that cowboys don’t care for jazz.

The sacrifice of our free thought to these features renders debate even more futile because a circular reasoning begins to take hold and all of a sudden you begin to believe you are “the kind of person” who listens to The Doors (sorry not sorry Morrison fans). But really, there is no one essential punk, no one true cowboy. The West Coast Hardcore screamers would sneer in Dylan’s face while Patti Smith and New York art rockers welcomed him in loving embrace.

Now, I recognize that many of the debates around music are not meant to be won or even resovled. They are in fact more generative when left up for more debate. The economist Paul Romer uses this exact verbiage when describing debates with his wife over who better country rock guitarist is, Clarence White or Gram Parsons. The point is talk and share in love of the music, not empirically prove that White was in fact the better guitarist. It can be a lot of fun to debate these questions when we give up the game of using debate as a mind-changing mechanism and I often find that my cultural criticism is more on point when it comes from a space of free play and fun rather than the perch of disdainful critique.

I guess what’s needed is not the abolition of debate from the public forum but a healthy dose of humility; a recognition that such a form can only get us so far. I for one will welcome any of your musical hot takes and would love to debate them not because I know I’m going to change your mind, but because I love talking about music. In more serious debates, however, it’s important to keep in mind who is setting the terms, who is running the “You Might Also Like” machine. I’m not so paranoid as to suggest that elites deliberately sew discord in order to retain power, but I will stress that only debating is no way to do politics and our demands really ought to shift to those in power not towards our fellow citizens. Unless, of course, they actually like The Doors.

Ramble on!